When we unearth the secrets, we can find real treasure. **AWARD WINNER**

Written and Illustrated by Dulce Zamora

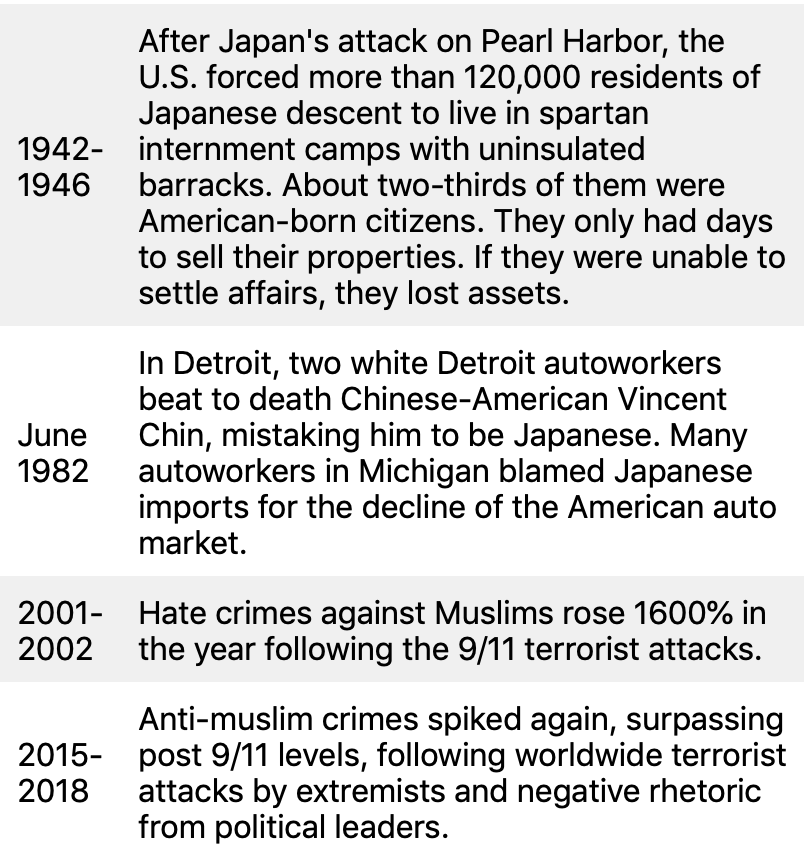

I am struggling to cope with the skyrocketing violence against Asians around the world. So are some of my family and friends. Some people have cried, recalling their own experiences being attacked or bullied. Some have worried about loved ones going out alone. Some have started carrying devices to protect themselves. When I think about these reactions, I recognize something I’m intimately familiar with as a 9/11 survivor: Trauma.

Over the top, you say? Each time I sit down to write this, I feel like either binge-watching hours of mindless stuff, devouring a whole pint of ice cream, or hiding under the covers. It took me a month to go from go from first draft to hitting “publish.” Mostly, I just want to forget about it. But I can’t. To do so would be to deny the trauma exists. To do so would be to give in to the shame of it. I don’t want people to see how much it affects me. I don’t want to be the complainer or the ingrate. I don’t want to make folks uncomfortable.

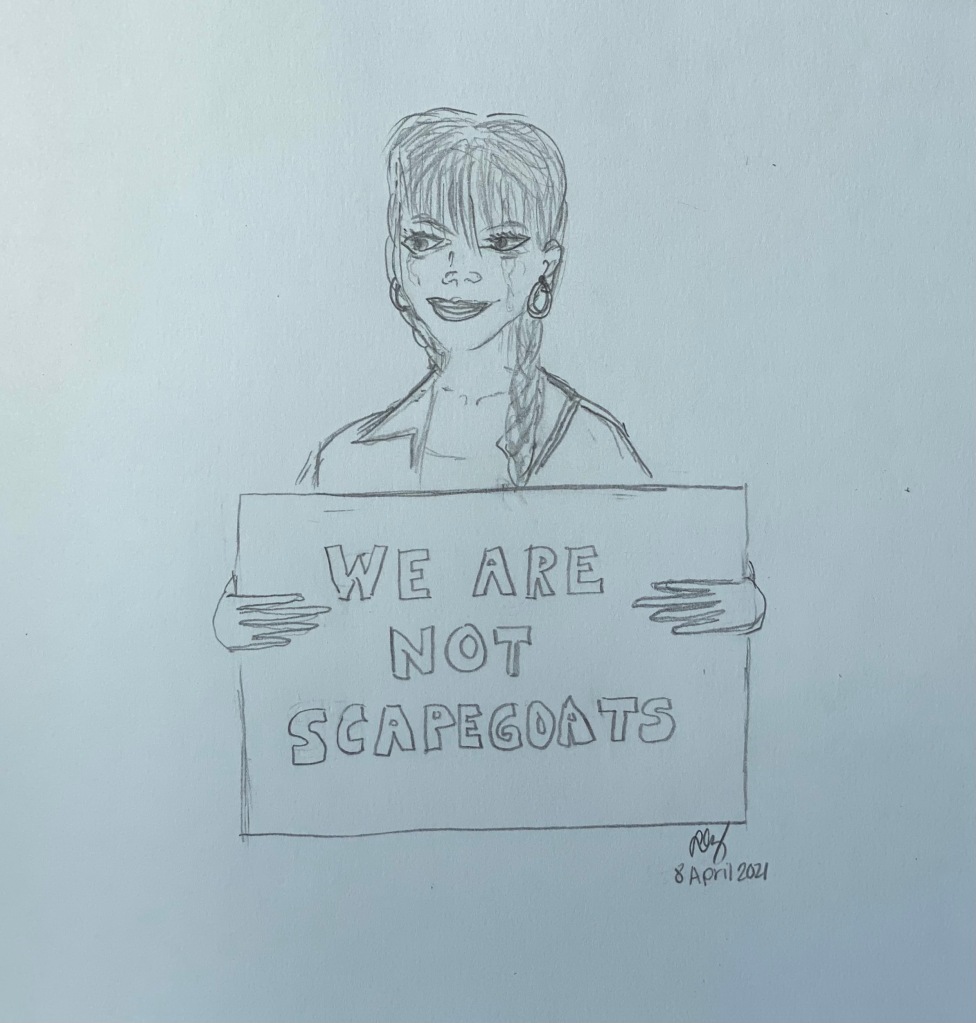

However, my avoiding the issue contributes to the problem. One family member said he detested the victim narrative in the anti-Asian hate campaign. I understood. We are certainly not helpless. Yet, the thought of sharing our experience does feel futile. Will it actually change anything? We’ve been dealing with aggressions against Asians for ages.

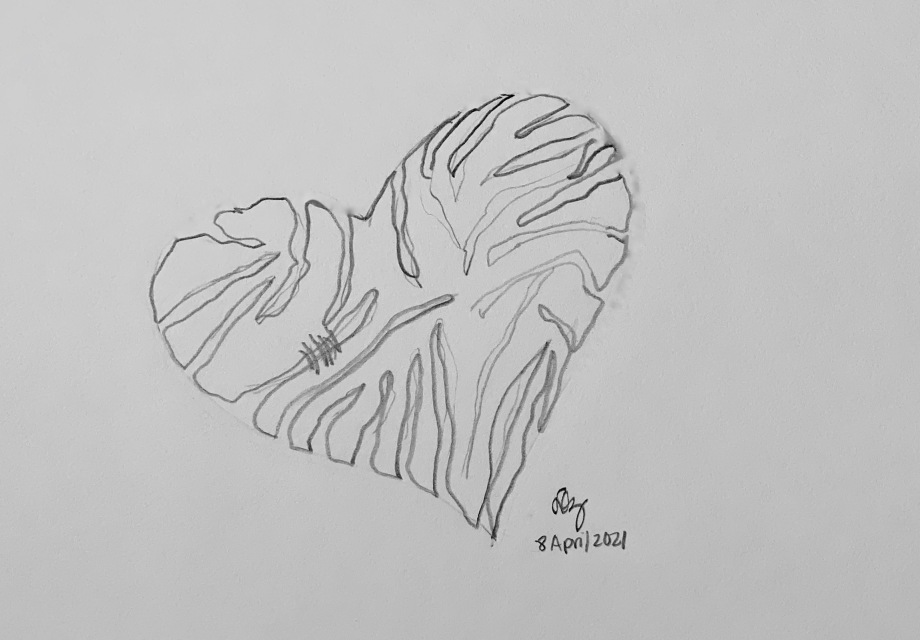

Recent incidents — from the Atlanta spa shootings, to New York City assaults, to San Francisco Bay Area thrashings — have reopened wounds that have long festered under silence, injustice, ignorance, and fear. These wounds have accumulated through time from seemingly harmless nicks at our identities as Asians. The incessant cuts have peeled off so much of our natural skin that we can sometimes feel raw, numb, or callous.

The assaults on my identity began when I was an elementary school student in the Philippines. The instructors forbade us from speaking anything but English in class. If we did, we had to drop coins in a can as penalty. A teacher told us to prepare for life in the United States. Ever since America’s 50-year-rule of the Pacific islands, which began in 1898 following 333 years of Spanish colonization, many Filipinos dreamed of moving stateside. They sought to escape the corruption and dearth of opportunities at home. After all, Uncle Sam promised to have the answers.

In a speech outlining his decision to annex the Philippines, U.S. President William McKinley declared that Filipinos were “unfit for self-government,” and it was America’s duty “to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them.”

When we finally migrated to California, it was still not okay to be who I was. Bullies told me to go back to China (because Asians have long been lumped together as Chinese). Kids made fun of my accent and dress, and called me “teacher’s pet” because I got good grades. You could say that my Philippine-based training prepared me well for academics — maybe too well, because I had already digested a lot of the things my 5th grade classmates were just beginning to learn, like multiplication tables and certain spelling words. The taunts and put-downs taught me that one must not shine too bright. Doing so was not “cool” and made other people feel bad. Movies also backed up the idea that people who excelled in class were either nerdy or obnoxious. So, I diminished myself to fit in. I even gave up a chance to run for class president one year, because a friend asked me to stand aside. She wanted to run and was afraid I’d win.

The taunts and put-downs taught me that one must not shine too bright.

As an Asian-American woman, I toiled for hours to become a television news producer and writer, but not without reminders of my supposed inferiority. Once, a colleague said, “You know, when [the news director] hired you, we all thought he was being cheap. You didn’t turn out too bad.”

I thanked him for the compliment, but did not yet have the confidence to ask why I was a cheap hire. Was my value less than other producers because I was a woman? An Asian? Or both? Did people think I was younger than I actually was (Asian genes)? I was still at the beginning of my career, but already possessed significant work experience. Prior to my hire, I had won an award as one of the most promising minority journalists in the country. I also received an award for health news segments I produced for my show. Apparently, awards and work experience don’t translate into dollars.

I tried to tell a good friend about the incident some years later, but she said my coworker probably meant something else. My friend likes to believe the best in people. That is a trait I love about her. However, I felt dismissed. My concern was somehow invalid because it did not fit the comfortable narrative. That particular wound cut deep because it came from a loved one.

These things don’t just happen in America. While backpacking through Italy, men threw unabashed lustful looks and catcalls my way. Strangers pinched my cheeks, calling me bella as if that gave them a mandate to touch me. Local teenage boys circled a Korean friend and me on the beach one day, slanting their eyes and mocking us with pretend Chinese words. A couple of days later, a muscular hostel security guard sexually assaulted the same friend. She was too timid to fight back. I screamed for him to get off of her, and urged the security guard’s buddy to step in. Thank goodness the friend helped so we could escape.

You would think I’d get better treatment as an Asian woman in Asia. However, that has not always been the case. Last year, my daughter and I were walking to school in Singapore. A car pulled up close behind us and blasted his horn. With my hands, I indicated he had physically gotten too close to us. I also pointed to a clearing ahead, indicating that if he had only waited a few seconds, we would have been out of his way. In our long, narrow cul de sac, it was common for everyone to walk on the road.

“You don’t belong here!” the Asian male driver yelled. I froze, but decided to give the man the benefit of the doubt. Maybe he meant to say that I don’t belong on the road.

“Using the sidewalk is really for your own good,” the driver’s female companion said in an apparent effort to diffuse tension.

“There’s no room,” I said, pointing to the open house gates, and garbage and recycling bins blocking the pedestrian lanes.

My daughter and I walked ahead toward school. A man who was walking on the street behind us stopped to talk to the driver. A few minutes later, when we were about to cross the street, the same driver pulled up next to us and yelled again, “You don’t belong here!”

By that time, we were standing on a less narrow stretch of the sidewalk, across the street from the international school where my daughter attended.

“You don’t know us,” I said. “We have been in Singapore a long time.”

“You don’t belong here,” he repeated, putting out his hands like public speakers do when they’re trying to make a point. He looked toward the international school gates with a line of kids streaming in for the day. He sighed and said, “You all don’t belong here.”

Then, he sped off, narrowly missing someone trying to cross the street.

I’ve heard variations of “You don’t belong here” many times, but it was the first that my 11-year-old daughter was with me. It pained me to realize that this was just the beginning of her hearing these type of messages.

“You don’t belong here!”

As an Asian-American expat in Singapore, I felt vulnerable. Even though we had lived in the country for more than a decade in total, even though my daughters were born here, and even though we had been contributing members of society, we were still viewed as outsiders. That morning, even though we looked Asian, my daughter wore a school uniform that indicated she had foreign ancestry. In this post-pandemic world, many nations have gone into self-preservation mode: Citizens come first. Everyone else is seen as a threat to jobs and security. This phenomenon has happened worldwide during other crises in history.

A Singaporean friend said it’s possible that when the irate driver saw me — an Asian woman — he saw an easy target for his rage. I don’t know for sure how he perceived me, but in this region of the world, being Filipina does have challenges. Since many Philippine women work here as domestic workers, I am often mistaken as the help, particularly when I’m with my oldest, who has relatively fair skin and has more Chinese features from my husband’s side. It is not uncommon for clerks to be shocked that I have a credit card, or to accuse me of stealing something. To protect myself, I make it a point to wear nice dresses, to fix up my hair, to wear jewelry, or to throw on a little lipstick. The messy hair bun and yoga pants that many Western mothers adopt do not work for me here if I want to be taken seriously. Sometimes even dressing up does not work. Sometimes, in order to earn respect and acknowledgement, I initiate conversation so people can hear my American accent.

Maybe some people don’t talk to me because they are just shy. Or they sport what may seem like condescending looks in general. That’s the messed up thing about experiencing second-class treatment. We become suspicious of others and ourselves. Are we being paranoid? How do we act? Are we part of a system that assigns worth based on race and class?

Once, when my children were babies, I went to a maid agency to interview people. I needed help with the housework. There were a couple of helpers who refused to meet with me, because they said I wasn’t an expat. When the agent explained that I was an expat, the women said they only wanted to work with white expat families.

When I’ve shared this story, people have said “I’m spoiled” or have first-world problems. They focus on the fact that I can afford a helper, and, somehow, that privilege strips me of my humanity. They don’t know that help is commonplace in Asia and the Middle East. They don’t know that their comments trivialize my journey toward success. They fail to realize that when I am minimized, my community gets knocked down, too. When I shine, my community shines, too.

All of my life experiences could well have other explanations. They could be disparate events. However, to dismiss all of them as separate from the other would be to disregard the collection as a whole. Overall, the world has told me — Asian-American woman — that:

I don’t belong.

I don’t matter.

I am not good enough.

I am invisible.

I must play small.

Asian women often find it hard to distinguish between the race-based slights and the gender ones. The assaults are often intertwined. We hear them in explicit and implicit ways. We hear them in different parts of the globe, even within our own “safe” communities. We say them to ourselves, using ‘I’m not enough‘ or ‘It’s not a big deal’ as reasons to remain silent. We don’t want the attention. We don’t want anyone feeling sorry for us. We don’t want to appear angry or crazy. We want to focus on the positives instead on dwelling on what makes us feel bad. We don’t want to compromise our relationships, our social standing, or our jobs. We also pride ourselves in being stoic and tough despite the pain.

However, when we remain silent, we leave every man, woman and child to navigate the minefields on their own. We don’t provide warnings even though we know the crippling missives are out there. We encourage our young to invalidate their thoughts and feelings. We tell them not to trust themselves. We lose chances to educate others.

When we share our hurts, we can help Asians and non-Asians build a common language toward a more equitable and compassionate society. People around us can be allies. Or, at the very least, they can be informed. We can stop internalizing the attacks on our identity. We can call out unacceptable behavior. We can be kinder to ourselves and to others. We can stop passing on the burden of silence to the next generation.

These sentiments are not representative of everyone, of course. Just as not every Asian is Chinese, not all Asians have the same experiences. However, many of us do feel dismayed about the current spike in Asian hate. Many of us don’t want repeats of violent, hate-filled history. Instead of enduring more aggressions, we can speak up for ourselves and for others. We can do our part in authoring real-life stories filled with love, tolerance, and compassion. We can help each other shine.

© 2021 Windswept Wildflower

Thank you for sharing and writing about your experience so beautifully. Though I haven’t been through the exact same situations, I can relate to the pain and trauma from what I’ve experienced myself. It does help to hear others’ stories and know we are not alone. I take inspiration from you and other writers to tell my own stories of discrimination someday. Even if it is viewed as more noise added to the “victim narratives,” I know it will help me process how what’s happened to me is impacting me now. And hopefully, that will help someone else … so the pattern of empathy continues.

LikeLiked by 1 person